Montessori Teaching Method Tested On Normal Children

by David Vachon

Reprinted by permission from the February-March 2007 issue of the

Old NewsIntroduction by Dr. James J. Asher

I was fascinated that Dr. Maria Montessori was the first woman in Italy to earn a medical

degree. She graduated from the University of Rome's School of Medicine in 1896 at the age of

twenty-six.

Her first job was working at the university's medical clinic treating intellectually handicapped

children who were billeted in an insane asylum. She discovered that no medical procedure at that

time was effective in helping these children.

By trial-and-error, she stumbled upon something that worked: I call it a “brainswitch” from the

children's left to their right brain with tactile activities such as touching and grasping objects. The

children used their fingers to (a) fit wooden shapes into cutout spaces, (b) use button boards for

practice in buttoning and unbuttoning, and (c) manipulate laces by tying and untying.

Children also sorted objects of different sizes and textures.

Normal chi ldren in publ ic school could also benef it

Next, it occurred to her that normal children in public schools could also benefit from tactile

activities. Here is her complete story that dramatically illustrates the power of brainswitching

from the left to the right brain. There is still another interesting explanation for the impact of

motor activity on learning. Research using brain scans by Dr. Melvyn A. Goodale and his colleagues

suggests that motor behavior including tactile was thousands of years ahead of visual perception

in evolutionary development. Tactile stimulation may be tapping into a primitive sensory system

that is a powerful force in human behavior. (For more on this theory, see my review of the

Goodale research by going to

This is a fun read for parents and teachers. For other exciting articles about science, history,

technology, and invention, I am pleased to recommend that you and your students will enjoy

every issue of Old News. Ask your school librarian to order a subscription. (See ordering details at

the end of this article.)

Maria Montessori was the first woman to earn a medical degree in Italy: she

graduated from the University of Rome's school of medicine in 1896 at the age

of twenty-six. While working at the university's psychiatric clinic, she began

treating intellectually handicapped children who were being held in an insane

asylum. She was familiar with the various "cures for idiocy" that were prescribed

in the medical literature of the day, but she found that no medical treatment

had any effect. The children improved only when she used the purely educational

treatments advocated by Edouard Seguin, a French physician who had

established schools for the intellectually handicapped in France and the United

States. In his 1866 book,

importance of developing self-reliance and independence in the intellectually

disabled by giving them a regimen of physical and intellectual tasks.

www.tpr-world and then click on TPR Articles.)Idiocy and Its Treatment, Seguin had stressed theMontessori developed a teaching system that combined the ideas of Seguin and others with her own

insights. She found that by emphasizing physical and tactile skills, she could capture the children's interest.

She gave them wooden cutouts of different shapes that could be felt with the fingers and set into

corresponding cutout spaces; button boards to practice buttoning and unbuttoning; laces to be tied and

untied; and objects of different sizes and textures to be sorted.

As the first accredited female physician in Italy, Montessori had become a celebrity. She decided to use her

fame to promote schools for the intellectually handicapped. By 1890 she had raised enough money to set up a

teacher-training school in Rome. As director, Montessori supervised student teachers in three classrooms.

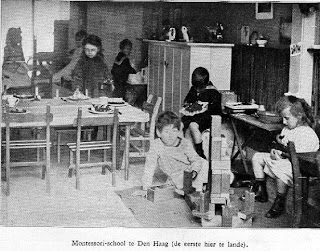

Children moved about the classroom from one activity to

another or stayed in one place working with one set of materials

until they had mastered them. Because the children were doing

interesting things, discipline ceased to be a problem, and they

began acquiring useful skills.

Montessori continually modified the materials as she

discovered which ones were most effective. When an

eleven-year-old girl could not learn to sew no matter how many

times she was shown, Montessori taught the girl to weave strips

of paper together to form a mat.

Once the girl had learned to weave, Montessori led her back to her sewing. Montessori wrote: "[I] saw with

pleasure that she was now able to follow the darning. From that time on, our sewing classes began with a

regular course in weaving."

Montessori realized that she could apply this same principle of tactile learning to writing. Rather than

starting off by showing children how to write cursive letters, she gave them a set of letters made out of wood.

The children touched and traced the shapes of letters with their fingers before trying to reproduce those same

shapes in writing.

All the students at the school had been classified as deficient and

uneducable, but visitors from the ministry of education were delighted

with the progress the students made. Some even learned to read and

write, and they passed the same exams as students in the regular

system.

Because her teaching methods blurred the distinction between

playing and learning, Montessori began to think that they might work

equally well on children of normal intelligence. After two years at the

school for intellectually handicapped children, she resigned as director

and returned to the University of Rome to study education. During

this period she visited elementary schools where she found that

children were "like butterflies mounted on pins…fastened each to his

place, the desk, spreading the useless wings of barren and

meaningless knowledge which they have acquired."

Montessori disapproved of the enforced silence and immobility, the

use of rewards and punishment, and the strict discipline in public schools. As a doctor, she was also appalled at

the poor sanitary conditions.

She was eager to try out her teaching methods on children of normal intelligence, and in 1906 she got the

chance. She was approached by Edouardo Talamo, director of a housing project for working-class families in

the San Lorenzo area of Rome. Talamo's tenants were mostly working couples with children. The preschoolers,

who ranged from three to six years old, were scribbling on walls in corridors and causing mischief, while their

parents were at work and their older siblings were at school. Talamo asked Montessori if she would start

classes for these children right in the tenement buildings.

There were between fifty and sixty

preschoolers in the tenement that

Montessori selected as her pilot project. If

the first project worked, Talamo had sixteen

other buildings in San Lorenzo to which the

project could be extended.

Montessori enlisted the financial support

of wealthy ladies who donated toys,

teaching materials, and money. She hired a

forty-year-old woman who had not been

trained as a teacher to lead the class under

her own guidance and direction. The

so-called Casa dei Bambini, or "Children's

House," opened on January 6, 1907.

At first Montessori instructed the

teacher to provide the children with toys and educational materials but not to teach them anything. Montessori

wanted to see what they would do on their own. Montessori and the teacher found that the children soon tired

of the less challenging toys such as the balls, dolls, and wagons, but they showed sustained interest in the

educational materials. Unlike the intellectually handicapped children, these students began immediately putting

the wooden circles, squares, and triangular shapes into the correct spaces in a wooden tray and repeating the

activities with great concentration.

Montessori intended to allow the children to work independently but

responsibly. She replaced the classroom's tables, chairs, and cabinets

with child-sized furniture, including small washstands where children

could use soap, water, and towels. Materials were housed in cabinets low

enough for each child to access, allowing them to take out materials and

put them back when they were finished. As a result, the students largely

taught themselves, while the teacher watched them and provided them

with materials appropriate to their stage of development. Activities such

as growing plants, caring for pets, preparing and serving meals, and

gymnastics all played a part in their day.

When critics objected that there was a lack of discipline, Montessori

responded: "A room in which all the children move about usefully,

intelligently, and voluntarily, without committing any rough or rude act,

would seem to me a classroom very well disciplined indeed."

Montessori instructed the teacher to pay close attention to each student's behavior, not allowing any of

the children to push their companions or put their feet on the desk. Children who continually misbehaved were

expelled, but they were few in number. Montessori conferred regularly with parents about the progress of their

children.

Three months after the first school opened, Montessori opened a class in a second tenement. Educators,

journalists, and royalty all visited the schools. When Italy's Queen Margherita visited the school, the children

greeted her politely and then quickly got back to their activities.

During the first semester, Montessori did not teach reading or writing, but

she thought her students were capable of it. She decided to begin teaching

these skills in the fall term. She knew that first-graders in the public schools

would be starting to learn to read and write at the same time, thus allowing

her to compare her results with those in the public system.

She had additional sets of cardboard and wooden letters made up, and she

allowed the children to manipulate those letters as she had done with

handicapped children. By Christmas of 1907, when the six-year-old first

graders in the public system were still practicing penmanship to prepare them

to learn to write, the Montessori four-year-olds were writing. Montessori's

success brought favorable newspaper articles, and soon the Italian public

became interested in her system.

In 1908 three more schools were opened, each providing further evidence

that Montessori's methods worked. Montessori was a charismatic speaker who

inspired people to follow her. She began training new teachers. In 1909 she

wrote her first book,

applications of her educational theories. She concluded: "Our children are

noticeably different from those others who have grown up within the gray walls of the common schools. Our

little pupils have the serene and happy aspect and the frank and open friendliness of the person who feels

himself to be master of his own actions."

The Montessori Method, to explain the origins andThe Montessori Method

translations were published in other countries. Educators from England, France, Canada, the United States, and

elsewhere visited Italy to learn about Montessori's methods. In 1912 Mabel Hubbard Bell, wife of Alexander

Graham Bell, and Margaret Wilson, daughter of President Woodrow Wilson, formed the American Montessori

Association. By the following year, there were nearly one hundred Montessori schools in the United States.

Today there are Montessori societies throughout the world and thousands of Montessori schools. Many

currently accepted ideas in education stemmed from Montessori's work, including the importance of early

learning, appropriate educational materials, small-scale furniture, the open classroom, strong parent

participation, and a stimulating learning environment. Maria Montessori continued to spread her philosophy of

education worldwide until her death in Holland in 1952, at the age of eighty-one.

SOURCES:

Kramer, Rita. Maria Montessori: A Biography. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1976.

Subscribe to Old News.

A one-year subscription to Old News (six issues) costs $17.

A two-year subscription (twelve issues) costs $33

Send your name, complete address, and phone number to:

Old News, 3 West Branch Blvd, Landisville, PA 17538-1105

Phone: (717) 898 9207 |

sparked international interest; within months it was being widely read, andwww.oldnewspublishing.comSorry, but Old News is unable to accept subscriptions outside of the USA.

To learn more about stress-free learning with TPR, visit

You can order the following Asher books online, at

www.tpr-world.com and click on TPR Articleswww.tpr-world.comAsher, James J.,

Learning Another Language Through Actions (6th edition).Los Gatos, CA., Sky Oaks Productions, Inc.

Asher, James J.,

Brainswitching: Learning on the right side of the brain.Los Gatos, CA., Sky Oaks Productions, Inc.

Asher, James J.,

The Super School: Teaching on the right side of the brain.Los Gatos, CA., Sky Oaks Productions, Inc.

Asher, James J.,

famous scientists and mathematicians.

The Wei rd and Wonder ful World of Mathematical Mysteries: Conversations withLos Gatos, CA., Sky Oaks Productions, Inc.

Asher, James J

., A Simpli fied Guide to Statist ics for Non-Mathematicians.Los Gatos, CA., Sky Oaks Productions, Inc.

Asher, James J.,

Pr ize-winning TPR Research (CD and Booklet).Los Gatos, CA., Sky Oaks Productions, Inc.

To communicate with the Dr. James J. Asher with your comments or questions, his e-mail is: tprworld@aol.com

تعليقات

إرسال تعليق